She was always the storyteller.

She could make them up on command. Anytime. Anywhere.

I remember one summer afternoon in 1968, we were waiting in the car while Mom was in the grocery store. It was warm and the windows were down, letting in a cool south Seattle breeze.

“See that man right there?” she asked me. “The sweaty one with the blue shirt and the frown?”

“Yeah,” I said.

“He just came to the store after murdering his family.”

My eyes widened at the thought, but something wasn’t right.

“I don’t see any blood,” I challenged.

She smiled, having anticipated my objection.

“He poisoned them. Rat poison. It made them sick and they puked all over the house as they died. It was then he realized he forgot to buy cleaner to wipe things up so nobody knows! That’s why he came to the store.”

“Wow!” I said.

I watched with wide eyes as the man walked into the store. Before, he seemed like an ordinary grown-up. But now his every move seemed sinister and evil.

–

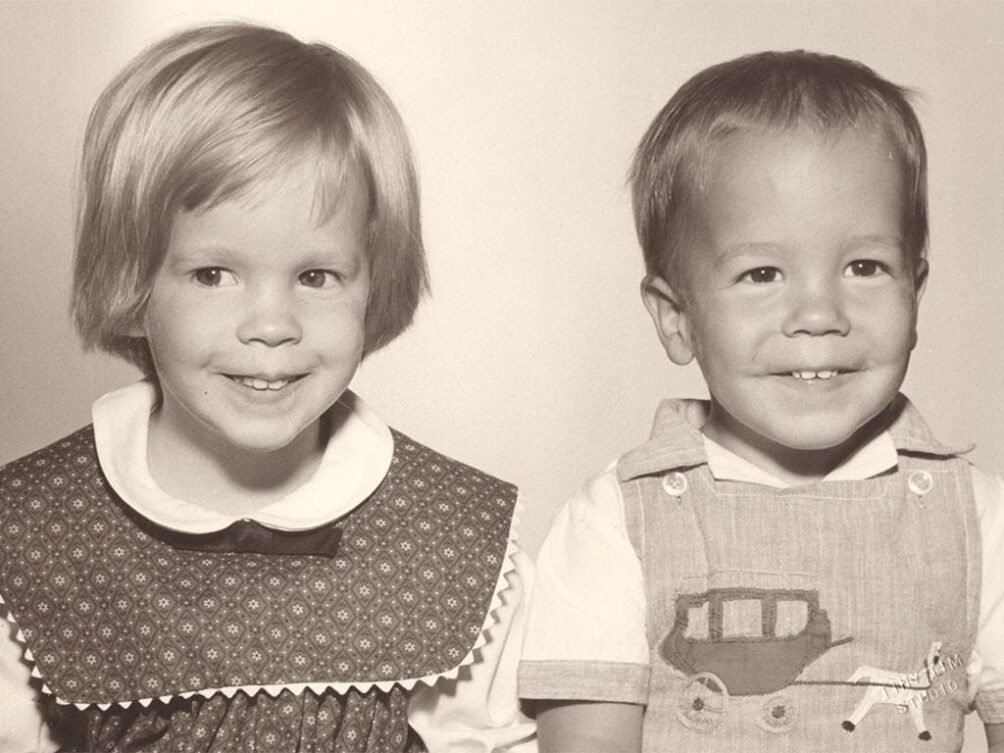

She was like that. Two years older and always a step ahead.

Her imagination was always better than mine. She could make up stories of random people she met; even imagine their back stories and motivations for whatever we saw them doing. But she never committed anything to paper. It was just a game, something to do to pass the time.

As she grew older, that quick mind got her in trouble at school and at home. The ideas and thoughts just naturally flowed out her mouth without a filter. The resulting conflicts soured her on academics and transformed her from a bright student to a foul-mouthed rebel.

In her last years of public school she was constantly being expelled. She began doing all the popular drugs. The fights at home with our parents escalated from verbal to physical.

–

But back when we were kids in the car on that hot summer day, she was still the master storyteller.

“Do it again!”

“Okay. See that old woman with the big tote bag?”

“Yep!”

“She’s been wandering the streets aimlessly from town to town for years. She’s so old she forgot who she is anymore. And in her bag… you’ll never guess what she has in her bag.”

“Ummm… her cat?”

“Nope. Guess again. You’ll never get it.”

“A candy bar!”

She looked at me with disappointment.

“You can do better than that. Guess!”

“I’m only six!” I protested.

“And I’m eight. So what? It’s a big bag. Guess!”

“A baseball glove and a ball!”

“Nope! You want me to tell you?”

“Yes! Tell me!”

“In that large bag, the old woman who wanders from town to town because she forgot who she is, carries…”

“What? Tell me! What does she carry?”

“In that bag she carries her soul!”

I tilted my head and squinted in confusion, not sure what a soul was.

“Is that like a ghost?”

“Yeah! Just like a ghost,” she agreed quickly. “And she uses it to scare people into giving her food.”

I looked at the old woman, suddenly afraid.

“I hope she doesn’t come near our car. We don’t have any food to give her.”

“Don’t worry. She only uses it on people who are selfish.”

“How does she know who’s selfish?”

“She doesn’t. Her soul knows.”

Frequently selfish myself, I didn’t want to think anymore about the old woman with the ghost in her bag looking for selfish children to scare.

–

At eighteen she left home and I rarely saw her.

She still had the gift, but even with her amazing imagination and storytelling ability, not even she could have imagined what would happen five years later in 1983.

It started with an argument with her boyfriend in a tavern. Whatever it was about, the result was an all-encompassing anger at the man.

The stupid bastard!

“F—k you! I’m walking home!”

Spilling the beer, she stood up from the table and staggered to the door of the tavern, tossing a few curses at him on her way out.

He stayed behind to finish the pitcher. Money was tight and he didn’t want to waste the beer.

She weaved down the sidewalk, more drunk than usual. Distracted while re-playing the argument in her head, she walked right past the turn to the street that would take her north to their apartment. Instead, she walked west down the hill, past the hospital until she came to the highway on-ramp heading north.

There she realized her mistake. But the highway went in the right direction, so instead of going back up the hill to the appropriate road, she staggered down the on-ramp. In her impaired state, she convinced herself she would be safe walking a mile along the shoulder until the next exit, which was near their apartment.

At about that time her boyfriend finished the pitcher, and went out to his truck.

“Damn her!” he said to nobody as he got in the pickup. He fumbled and dropped his keys, picking them up off the floor.

Drunk? Yeah, sure. But he’d done it before. And it was only a mile or so.

He pulled out and came to the road that would take him north to their apartment.

“Hell with that! I ain’t givin’ her a ride, and I’ll never hear the end of it if I pass her walking on that road,” he reasoned. “Get home first and claim the bed. She can damn well sleep on the couch. I’m taking the highway.”

–

Back in 1968, sitting in the car waiting for mom to finish grocery shopping, I asked my sister the storyteller for more.

“What about those kids sitting in that car?” I asked, pointing. “The red one over there.”

“They’re orphans,” she said without missing a beat.

“Orphans?”

“Yeah. Kids whose parents died,” she explained. “But these kids’ parents didn’t die.”

“They didn’t?”

“Nope. They abandoned them.”

“Abandoned?”

“Just left them all by themselves. Only a couple hours ago. They parked the car and told the kids to wait, just like Mom did with us. But instead of going shopping, they slipped out a side door and caught a bus. And they’re never coming back.”

Suddenly concerned, I said, “Mom wouldn’t do that, would she? She wouldn’t abandon us.”

“Who knows? You were being a real jerk, wanting to go in the store with her. Maybe this is her chance to get away from you,” she paused dramatically, “forever.”

She quickly looked out the side window. I couldn’t see her face.

A few minutes later Mom returned with arms full of groceries. She was puzzled to see my sister in the passenger seat casually looking out the window wearing a face frozen in bland innocence; and me in the back seat, red-faced and bawling.

–

Years later, still angered at her boyfriend and staggering down the highway, she stopped to puke in the weeds along the shoulder.

Getting back up, dizzy and drunk, she resumed her trek, but she was severely off-balance and staggered into the left lane where the vehicle struck her going fifty-miles an hour.

She flew nearly a hundred feet like a rag doll and landed on the hard asphalt, lacerating her body, breaking bones, causing numerous internal injuries and most tragically slamming her head hard first into the truck and then the highway.

It was the pickup driven by her boyfriend.

He crushed the brakes, coming to a stop several feet away from the mangled body.

He recognized her. And he panicked.

Picking her up, he placed her in the bed of his pickup and raced back to the hospital.

The emergency staff did what they could. Hours later the police arrived to get a statement. At that time his blood alcohol registered below the legal limit.

Legally he wasn’t drunk. But there were questions.

The second-guessing was relentless, and completely pointless as she lay dying in the ICU.

Later that week, we were at the hospital to say goodbye to my sister.

Standing beside her bed, shortly before the life support was disconnected, I could not think of what to say. I listened to the machinery of a counterfeit life whistling and beeping, keeping her body alive. Her brain was dead, but her organs were meant for others.

I placed my hand gently on her wrist and thought of that day in the grocery store parking lot, and all the other times she told her stories to me. I remembered how she made people seem different. Sometimes amusing. Sometimes sinister. And at other times sad and tortured. Such an incredible gift, and nothing ever written down.

The memory brought a smile to my face. And tears.

A tear fell from my cheek onto the cold white pillow beside her, and was immediately soaked up in the fabric, becoming part of the pillow.

It struck me then that as a child, her stories soaked into me, becoming a part of my identity. I was entertained by them, certainly. But her stories also changed me, had moved me just a little outside my childish selfishness. She shifted my point of view just enough to consider other people’s thoughts and motivations; their joys and tragedies; what made them angry; and what frightened them. From her stories I learned to see the world in different ways.

It was a last gift from an older sister to a little brother – this ability to see, to empathize. To imagine.

As I stood in the cold hospital room I thought of these things, and the inadequacy of “Goodbye”. Instead, I wanted to tell her that her gift would live on, however imperfectly, in me.

I bent to her ear and whispered, “I’m the storyteller now.”

–––––––––––

Dedicated to the memory of my sister, Teri Merryman, who died in October, 1983.

About the Author

Topdog is Steve Merryman, a retired graphic designer, illustrator, and unrepentant asshole. Steve can usually be found working on a portrait commission or some other artwork. Steve fills his days by painting, writing, shootin' guns, cuttin' trees, hiking with his dogs, and savoring a beer or two, all while searching for the perfect cheeseburger. He studiously avoids social media and is occasionally without pants.

Comments 4

What an amazing story. So raw and beautiful. Thank you for sharing and writing so eloquently about it. You ARE the storyteller AND the illustrator. Love you.

Author

Thanks, Sis! I appreciate the kind words.

Thank you.

Author

de nada