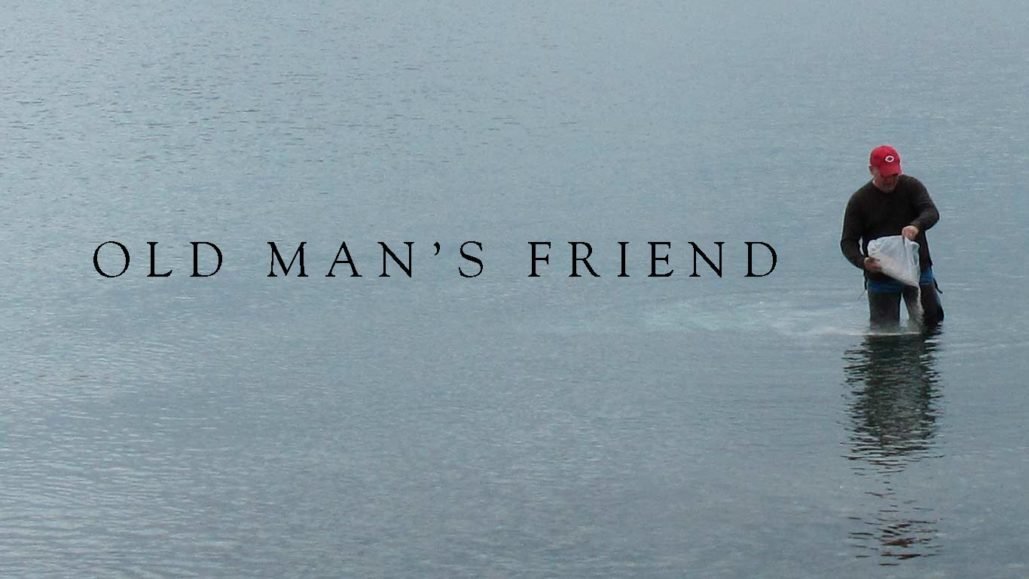

"I wish I could die of pneumonia."

It was a warm, May morning in 2007. I was driving Dad from his home in Sequim to Renton, on the other side of Washington state's scenic Puget Sound. We were on our way to Greenwood cemetery to inter my mother's ashes, and death was on Dad's mind.

"What?" I asked, baffled.

"They made me get vaccinated for pneumonia. Back then we all got shots at the fire station. I didn't think anything of it at the time. It made sense."

"Yeah, I suppose," I agreed. "The city didn't want a bunch of sick firemen."

"Yep."

A pause.

"And we didn't always go into the most healthy places."

"'Entering Healthy Places' wasn't exactly in the job description," I said.

He smiled at the comment.

"True, that."

I wondered where Dad was going with this line of thought. Was he confused?

Mom didn't die from pneumonia. She had Lupus. A weird malady causing her lungs to slowly crystalize. The official diagnosis was "congestive heart failure" because her heart was having to work twice as hard with half the oxygenated blood. One thing led to another and she had a stroke in July of 2006, which took away almost everything that made her Mom.

Dad never left her side. He rebuilt the house for wheelchair access. He fed her by hand. He gave her medication. He cleaned her diapers. He did everything.

He looked particularly haggard when I visited in October.

In the beginning, she had hope. They both did. But she didn't improve. Her brain was too damaged. She eventually lost that hope and in the end simply refused her meds, allowing nature to take it's course.

Six long, grinding months after her stroke, she died. It was Christmas Eve, 2006.

I thought about this as we drove to the cemetery with Mom's ashes in the trunk.

Retrieving his train of thought, Dad said, "Pneumonia is a gentle way to go. No pain. You just drift off. Fade away."

"I didn't know that," I said.

Mom's ashes were buried in Greenwood cemetery next to my older sister, Teri, who died in 1983 after being hit by a car on a highway while walking home drunk. She wandered into the oncoming lane at one in the morning.

After Mom died, Dad soldiered on for six more years. I think he spent most of the time preparing for his own death. All his possessions were put in order; his papers collected; all debts paid; nothing was left to chance.

It was like he knew.

He called me on my birthday in 2012.

"Well," he said after wishing me the best, "I know my expiration date."

"Huh?"

"Pancreatic cancer. Doctor gave me six months."

After I recovered my wits, "I'm sorry to hear that. How you holding up?"

"Not bad so far. My oncologist is a woman, and she's gorgeous! Makes me want to stretch it to seven months just for a sponge bath reward."

I didn't bother telling him nurses usually do that. He knew. He was just making a joke.

"That's the spirit!" I said.

"Hell," he said with a touch of fatalism in his voice, "you gotta die of something."

He made it three months. His second to last week was excruciating as the cancer ate through his torso. His last week was spent in a morphine fog in a hospice bed at home. On the mantle, a portrait of Mom watched over him. I'm not sure he recognized her. He died April 15, 2012.

But back in 2006, as we drove to bury Mom's ashes, he wanted to talk about pneumonia.

"A nice, gentle slide into oblivion," he said quietly.

"Dad?"

I was starting to get worried.

"You know what they call pneumonia?" he asked, looking at me.

"Dad, you okay?"

"You may not understand now. But someday you'll get it," he said looking past me at something only he could see.

"Okay, Dad. What do they call pneumonia?"

"The Old Man's Friend," he said almost to himself, and turning, watched Puget Sound slide by in the window.

©2020 SIGMADOG LLC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Comments 3

I watched as my father slowly lost memory of everything in his life. Many a fate is kinder.

My thoughts are with you, my friend.

Author

My dad went fairly quick (just a few months), but it was physically painful as the cancer ate away at him. I can’t imagine helplessly watching a slow decline as in your situation.

I take a snort (or five) of whiskey every Father’s Day and think of him. I miss the old fart.

Mine made life look so much easier.